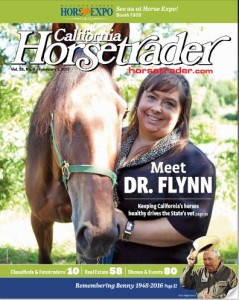

California’s ranking equine vet has a passion for horses — and also their well-being. This winter’s containment of an EHV-1 outbreak in Los Angeles County put Dr. Flynn and her California Division of Food and Agriculture (CDFA) colleagues on the frontlines — and the importance of public awareness in the headlines.

California’s ranking equine vet has a passion for horses — and also their well-being. This winter’s containment of an EHV-1 outbreak in Los Angeles County put Dr. Flynn and her California Division of Food and Agriculture (CDFA) colleagues on the frontlines — and the importance of public awareness in the headlines.

Horses surround your work. How have they surrounded your life?

Horses are my passion. I grew up on a family Standardbred racehorse farm in South Grafton, Mass. I learned to drive “Terry Anns Choice” at a young age and foaled out one of her colts on my own when I was 16. While growing up, I traveled with my dad to paddock horses at harness racing tracks across New England and New York.

My first horse appeared on my back doorstep as a gift one Christmas morning, “Strawberry Sundae,” a strawberry roan mare. We became a team and participated in 4-H and local fair horse shows. We also used to wrangle up the occasional Hereford beef cow that got loose on the family farm.

I am busy now with my career in regulatory medicine in California, but I look forward to my visits back east when I can jog a family racehorse. I hope to one day own a few Standardbred racehorses to carry on the family tradition.

Was there a turning point that sent you toward a career in public medicine?

When I was 11 years old, I watched one of our great broodmares, “Jo Jo Worthy”, die during foaling from a ruptured uterine artery. It was a turning point in my life. I knew then that I wanted to have a career protecting the health of horses. I pursued a veterinary education and my career focus has been to protect the health and welfare of horses.

What has been your path?

In 2002, I began a career in regulatory medicine with the CDFA, whose mission is to protect animal agriculture in the state of California. In 2008, I became the CDFA Equine Staff Veterinarian with responsibility for overseeing equine regulatory disease programs and managing the California Equine Medication Monitoring Program. This position has afforded me the unique opportunity to become intimately involved in equine health and welfare issues at the local, state, and national level.

It sounds as if your passions for both horses and public health have truly come together.

Yes, in the past five years my efforts to advance equine health through biosecurity outreach and education have been rewarding. In 2012, at the request of California’s Equine Medication Monitoring Program Advisory Committee, I made assessments of a variety of show ground facilities in California to evaluate the biosecurity practices and disease transmission risk factors and to make recommendations on common sense ways to protect the health of competition horses at equine events. These complied observations and recommendations led to the development of the Equine Biosecurity Toolkit for Equine Events. The toolkit has subsequently been distributed across the U.S and to 12 foreign countries. It was even used as a reference during the London and Rio Olympic equestrian events.

Representing state animal health officials on equine health issues is important to me, as I am making a difference for the horse. For the past five years, I have served as Vice Chair of the United States Animal Health Association Infectious Disease of Horses Committee and will become Chair of this Committee in 2017. I was also nominated to serve on the American Association of Equine Practitioners Leadership Development Committee, Infectious Disease Committee and Welfare and Public Policy Committee.

What inspired you to the reach the role you have today as the CDFA Equine Staff Veterinarian?

Honestly, my dad and my veterinarian uncle, Dr. Dan Flynn, are my inspiration. Their lifelong passion for the horse and their desire to ensure the health and well-being of horses in their care inspire me.

My father taught me that horsemanship starts with listening to the horse and forming a partnership. He firmly believes a healthy, well-trained horse can win a race on heart alone.

Many ask me, why government work? Honestly, I never thought my career would take me to a government position. Early on, I thought racehorse lameness work would be in my future. I soon realized the enormous potential impact a regulatory medicine position can have on the health of horses. For me, this pursuit has definitely been the most rewarding.

Clearly, you have strong convictions about your work.

It’s easy to wake up each day to work at a job you believe in and know you are making a difference. I strongly believe in the mission of the California Equine Medication Monitoring Program to ensure the integrity of public equine events in California through the control of performance enhancing drugs and permitting limited therapeutic use of drugs and medications. Personally, I believe that drug-related rules for performance horses are critical to protecting their health and well-being.

Growing up around racetracks and training facilities, I witnessed horsemanship and training techniques that sometimes compromised the health and well-being of horses. I very strongly support measures, like the implementation of drug rules and disease control regulations, to protect the health and well-being of horses.

California is immense, and agriculture is critically important. What role does the CDFA Animal Health Branch play?

The Animal Health Branch of the California Department of Food Agriculture is the State’s organized, professional, veterinary medical unit that protects livestock populations, consumers, and California’s economy from catastrophic animal diseases and other health or agricultural problems.

Branch personnel address diseases and other problems that cannot be successfully controlled on an individual animal or herd basis, but require state-wide coordinated resources.

With respect to horses, what are your team’s top objectives?

In short, our key goals are to keep specific diseases out of the State by implementing and enforcing entry requirements, by responding to disease threats with implementation of biosecurity measures and movement restrictions, and to providing outreach and education on best management practices to protect the health of horses to the horse industry.

CDFA Animal Health Branch personnel work to ensure the health of California’s equine population. We are responsible for developing and implementing effective animal health regulations and ensuring science-based disease control measures to control regulated diseases. Our priorities are to ensure that requirements for equine movements into the state are met, to monitor equine disease detections in the state, to mitigate threats and to effectively respond to detections of diseases of importance.

Our equine regulatory disease responsibilities include identifying and locating equids in the state with positive tests for regulated diseases, conducting epidemiologic investigations to trace and potentially test exposed animals, assessing and determining quarantine implementation and release parameters, implementing appropriate disease control methodologies, issuing movement restrictions when appropriate, and reporting disease investigation findings. Implementation of science-based biosecurity measures for diseases of regulatory concern is pivitol to protecting the health of the state and national equine population.

Success of programs would seem to rely on horse people knowing and playing their roles — from clubs and associations, to show barns, to individual horse owners.

Successful protection of equine health relies on collaboration and communication with all sectors of the equine industry. Everyone must do their part to protect the health of horses and the viability of the equine industry. Equine facility owners/managers should have a facility biosecurity plan in place that limits horse-to-horse contact, limits human contact with multiple horses along the barn row without use of hand sanitizer between horses and avoids the use of shared equipment unless it is cleaned and disinfected between use. Owners, trainers and grooms can monitor the health of each individual horse by taking temperatures twice daily and promptly report any clinical signs of disease or temperatures over 102°F to a veterinarian. Only healthy horses should be taken on public trails or sent to equine events where horses are commingled and the potential for close horse contacts exists.

Are there take-aways from the EHV-1 cases at the L.A. Equestrian Center at the end of last year?

California state law requires the reporting of Equine Herpes Myeloencephalopathy (EHM) cases to the California Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA) Animal Health Branch (AHB). CDFA investigates reports and takes regulatory action only after confirmation that the horse meets the criteria of the EHM case definition (positive EHV-1 laboratory tests and compatible neurologic clinical signs). In California, no regulatory action is taken when a horse with only clinical signs of respiratory disease is found positive for EHV-1.

Equine Herpesvirus Myeloencephalopathy cases became reportable in California in 2011. Since then, CDFA has investigated eighteen (18) EHM incidents in the state. To date, the LAEC, with 725 horses housed on the property, a large show facility, and public trail, is the largest and most complex of the EHV-1 incident investigations. I applaud the LAEC management, staff, owners, and trainers for coming together in response to the disease detection. Their responsiveness to regulatory recommendations truly demonstrated that they had horse health and the best interest of the horse as their priorities. I personally thank everyone involved for all their efforts.

It’s important to remember that EHV-1 is in the environment and horses are exposed to the virus early in life. Following exposure, the virus enters the horse and may remain viable without clinical signs of disease (latent). With latent infection, the horse can periodically shed the virus into the environment, where the virus likes cold damp places. Cases of EHV-1 infection then typically occur between October and March. At this time, there are two known strains of the virus, specifically the neuropathogenic strain and the wild type/non-neuropathogenic strain. The differentiation in strain types was based on research indicating that the neuropathogenic strain was more likely to cause neurologic disease in a horse. But it is important to know that both strains can cause clinical diseases affecting the respiratory, nervous and reproductive systems.

What do you see in the future of public health management in the horse world?

Looking to the future, regulatory medicine will continue to focus efforts on prompt diagnosis and response to equine diseases of regulatory importance, on development of improved rapid diagnostic capabilities for equine diseases, and on providing the equine industry with information on best management practices they can use to advance and protect the health of our valuable horse populations. Engagement of people at all levels of the equine industry and enhanced communication between regulatory officials and the equine industry will go a long way. Working together, we can be most effective in advancing horse health in the United States and abroad.

Leave a Comment

All fields must be filled in to leave a message.